View on

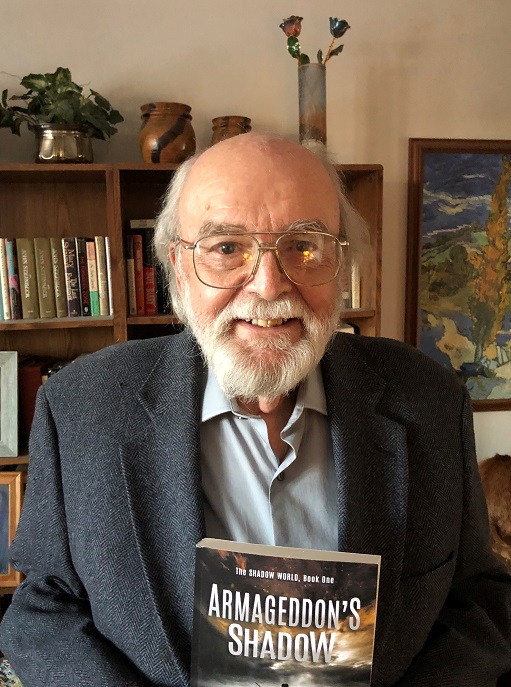

A Shadow over the Afterworld

January, 2025

Life, love and adventure after the pandemic…

In 2072, antibiotic-resistant bacteria cause a pandemic

that kills 90% of humanity. Armageddon’s Shadow

introduced us to members of a scrounger gang who

trade goods they find in the ruins with survivors in the

few settlements. Now, we follow the adventures of the

youngest gang member, John Moore, as he grows to

manhood and finds that the evils of the old world have

followed him into the new. So has the Shadow that

haunted his childhood and killed his loved ones.

John falls in love with two beautiful sisters, Alicia and

Jaclyn. After the abduction of Alicia and a desperate

chase to rescue her, he has no idea how to solve the

problems inherent in a love triangle.

But the sisters do.

This month's Free Read - a scientific mystery:

January, 2025

I Know the Answer - What's the Question?

I was frantically typing notes into my tablet about a new, exciting proof to try out when

she spoke to me.

“Pardon?” she said.

I looked to my left, disoriented as I often was when lost in a mathematical fog. As

always, I sat at the end of the bar, as far from people as possible. She had taken the barstool

next to mine, apparently because the after-work crowd filled most of the others.

“What?” I asked stupidly. She had a round face surrounded by ginger curls, bright blue

eyes and a broad smile. I quickly shut my mouth, which had been hanging open in a doltish

fashion.

“I'm sorry,” she said. “I thought you were speaking to me.”

“Oh, my. I'm the sorry one. I sometimes do that – speaking aloud when I can’t find a

solution or have a new idea.”

She chuckled. “That can be dangerous. You might disclose secrets you don’t want others

to know.”

Her humor was contagious. I smiled. “I'm afraid I lead too dull a life to have any

dangerous secrets. What did I say?”

“You don’t know?” Her smile widened. “You said, ‘Maybe I’ve been looking at it wrong,’

and started pecking away at your tablet keys like a madman.”

“Ah, yes. I just had an idea and wanted to get it down before I forgot it.”

“Did my question make you forget it before you got it typed in?”

“No, I got the gist of it down. I can work out the details tonight.”

“You’re going to work tonight? It’s already almost 6:30. And look.” She pointed to his

beer mug. “You still have a third of the beer left you had when I sat down. I drank a whole

one since then and I'm not a fast drinker, so yours must be warm and flat.”

“Well, I –”

“I always have two when I come in here in the evening, so I'm going to buy you one

while I have my second. Hey, Jack.” She raised her hand, holding up two fingers to the

bartender. In popular bars and restaurants calling themselves “efficiencies,” customers

ordered food, drinks and music from machines on their tables. They only saw the waiters

bringing their orders, who still expected a hearty tip. Murphy’s, a step above a “dive bar,”

relied on personable bartenders like Jack, who knew when a patron wanted conversation. I

valued him because he sensed the times I liked being left alone to work.

“Thanks,” I said. “I was going to go back to work, but I can’t let a beer go to waste.” I

downed the rest of my beer – it was warm and flat like she predicted.

“So,” she said, “you just come in here for a beer and go right back to your office?”

“I work at home on a special project that takes a lot of time. Sometimes, I need a change

of place and a little alcohol to work out a problem.”

“Are you some kind of scientist?”

“I'm a mathematician, trying to solve a problem that will help computer scientists and

other technical people. I think I'm close to an answer.”

The bartender arrived with our beers.

She sipped hers. “It’ll help you to get away from your computer for a while. What’s your

name, anyhow? Mine’s Meribel McGonigal. I prefer Mel.”

“What a poetic name! I'm Arthur Edelman. Art.” I had seen her here in Murphy’s before

when I came in for my beer break, always alone. I thought she had glanced my way a few

times, but that was unlikely, given my long, lugubrious face, shaggy hair and droopy brown

eyes.

I asked, “Do you work around here?”

“Yes. At the trucking company Algonquin Carriers. I type shipping labels, sort mail, keep

track of scheduling. You know, I'm a paper pusher. What kind of project are you working

on?”

“It’s a boring mathematical problem.” I couldn’t tell her anymore. Not that she looked or

acted like an industrial spy, but I couldn’t take the risk.

Taking the hint, she changed the subject to inconsequential things. I found her easy to

talk to and was glad to get my mind off the P versus NP problem. Her blue eyes sparkled

and I liked the sprinkle of freckles across her cheeks and upturned nose.

After a time, she said, “Are you hungry?”

“Yes, as a matter of fact.”

“If you like shrimp, the College Inn has a shrimp special tonight. Even though the

nearest ocean is over five hundred miles away, they fly them in, fresh-frozen, for specials.”

“I love shrimp. Let’s go.”

We finished our beers and went out. I could let my work slide for one night. She signaled

a cab and, after it arrived, input an address into its keyboard. It whisked us away, and fifteen

minutes later, we sat at a table in the College Inn. We ordered shrimp scampi.

She said, “They have a great pinot grigio that goes well with it.”

So we ordered a bottle of that.

Halfway through the meal, from behind, I heard the high-pitched voice of the only

friend I had made in the month I had been in town.

“Artie! Fancy seeing you here.” He knew I hated the nickname but insisted on using it.

I turned partway to face my portly friend. His little dark eyes, small mouth, and nubbin

nose looked lost in his fleshy face. The ends of his mustache quirked upward, much like

those of Frans Hals’ Laughing Cavalier, but the pointed end of his black goatee looked

vaguely Mephistophelian.

“Hello, Rollie. Here for the shrimp?”

“Just finished eating.” He was looking at Meribel.

I said, “This is Mer-, uh, Mel. And Mel, Rollie.”

“It’s Ed Rollingford,” said Rollie, “but I like Rollie better. Ed is so bland, don’t you

think?”

“Oh, there have been famous Edwards,” she said. “England had ten or eleven King

Edwards. Edward Teller helped develop the atomic bomb and later became the so-called

‘Father of the H-bomb.’ And Edward Morley was the first scientist to measure the atomic

weight of oxygen.”

“Why, uh, yes,” he said, surprised at her knowledge of Edwards. As was I. Mel was a

well-educated paper-pusher.

Rollie joined us for the rest of the meal, helping himself to the last of the wine but

ordering and paying for another bottle. By the time we left the College Inn and went our

separate ways, I felt pleasantly replete.

As I walked back to my rooms, my portable comm unit buzzed. The caller’s unfamiliar

number stunned me. Nobody outside of Szilard Enterprises should know I was here. I

didn’t even let my mother and friends know. I hesitated to answer but finally did; I had to

know if somebody had found my location who shouldn’t have.

Ben Delgado answered.

“Ben, what are you doing calling from this number?”

“I was afraid my comm got compromised, so I got a new one. How are you doing? Any

progress?”

“Yes, I thought of a new approach this afternoon. I'll pursue it in the morning.” I

laughed. “I myself got too compromised tonight. Too much wine with friends.”

“Friends? We didn’t send you to the middle of nowhere in the Midwest to make friends,

Art. You’re there to solve the P versus NP problem in isolation. To keep hackers from

copying your work.”

“Relax, Ben. These two aren’t scientists. They wouldn’t know what I was talking about if

I explained it. One is a bookkeeper who works for a trucking company, and the other is an

independently wealthy guy who collects bugs.”

“Well… okay, but watch yourself. When will you have something for us?”

“Tomorrow, I’ll send you an update on your commcomp, like I did last week. I won’t let

you know my new idea over it, though. If there are any agents in town, they can spy on me

with those minuscule drones. I assume they can hack the commcomp, which I only use for

messages, but they can’t my tablet.”

“I'm glad you’re careful. As always, I look forward to getting your message. When you

complete the project, it’ll make us the world’s richest, most important data-processing

company.”

“Okay, I'll have it soon.”

“That’s all for now, then. Bye, kid.”

“So long, Ben.”

Yes, solving the P versus NP problem would make Szilard the wealthiest, most sought-

after company in the world. Presently, there was no known way to quickly find an answer to

some questions, but ironically, if given an answer, it could be verified quickly. One example

was the traveling salesman problem. If he has a list of cities and the distances between each

pair of them, how does he find the shortest route enabling him to visit each city once and

return to the one from which he started? Once the salesman finally finds the answer

through trial and error, he can immediately prove it.

P stood for problems that took computers a long time to solve, and NP for those with

solutions that could be rapidly checked. If I solved P versus NP, this and countless other

insoluble questions would be speedily answered. If I could find a way for P to equal NP

instead of being versus NP, information technology would profoundly change. There would

be no gap between finding a problem’s answer and recognizing the solution once it's found.

Travel routing, increased production and scheduling would be optimized. No delays in

traffic or waiting for days for a package.

And if Szilard Enterprises had the solution, anyone with such a problem would have to

come to it.

And I would have the answers in a few days.

For a change, I went to sleep elated, either from my nearly completed project, the wine

or perhaps from thinking of Mel.

Rollie had invited me over to see his loft the next day, Saturday. I arrived at 10:00, as

agreed. The large main room served as the living and dining rooms, with a kitchen

separated from it by a counter. His furniture was scanty and scattered about haphazardly.

Dirty clothes, empty beer cans, pizza cartons and other miscellaneous refuse lay about. A

ladder led up to a mezzanine level, which appeared to be a sleeping room. His rooms

occupied the top floor of the building and the ceiling, studded with skylights, soared to just

below the roof.

The adornments on the wall piqued my curiosity: shallow, glass-covered boxes with

insects pinned to white backgrounds. I examined a couple of them, both inhabited by

beetles.

“Did you collect all these?” I asked, waving a hand to encompass the dozen or so

exhibits, remembering him saying that was his hobby.

He was beaming. “Yes. I have to give it up in the summer; it’s so hot, but I'll be back out

now that it’s October while you’re hacking away at your commcomp. My dear Aunt Martha,

who raised me, God rest her soul, hated my bugs but left me her fortune anyway.”

“At least it gives you something to occupy your time.”

“Oh, I have other activities. But here, look at this picture of my hero.”

A photo of British evolutionary biologist and geneticist JBS Haldane hung on the wall.

Under it was one of his most famous quotes: “It is my supposition that the universe is not

only queerer than we imagine, is queerer than we can imagine.”

I said, “He liked insects too, didn’t he?”

“Yes. Especially beetles. When asked what his search for beetles told him about God,

Haldane said He “must have an inordinate fondness for beetles.” There are more species of

beetles – phylum Arthropoda, class Insecta, order Coleoptera – than any other group of

living animals. About one out of every four animal species on Earth is a beetle.

“But, say, Artie, I was waiting for you to have coffee. Would you like some?”

With our coffee, we sat in comfortable chairs and discussed his favorite scientist’s many

talents and achievements for a while.

At last, he said, “Now you know everything about me, while you’re a complete mystery

to me. Tell me about yourself.”

“There’s nothing interesting to tell. I grew up in an academic family. My mother and

father had positions at the University of California, Berkley. Father died of a rare heart

condition. Mother, retired, still lives in Berkley. I got my Master’s at MIT.”

“So, what are you pecking away at on your commcomp or tablet day and night?”

I shook my head. “It’s not work. I went back to MIT for my PhD, and now I'm working

on my dissertation.” Which was partially true.

“Wow! You could be another of those young geniuses like Einstein, who won the Nobel

prize at age twenty-five.”

“It’s too late for me. I'm already twenty-nine.”

“Can you tell me the subject of your dissertation?”

“Not till I finish it. That would be bad luck.”

We spent the next few hours chatting agreeably. Rollie wasn’t as foolish as he had

appeared. He had some college and had gained a great deal of knowledge on his own. For

lunch, he prepared two humongous, delicious sandwiches piled with pastrami, Swiss cheese,

marinated onions, pickles, leak lettuce, and yellow mustard on rye bread, which explained

his broad girth. I couldn’t eat all mine, but he wrapped it and made me take it with me.

At home, I sought one of my own favorite scientists on that wonderful machine that

allows us to communicate long distances, solve intricate mathematical and scientific

problems and play games. We can also access virtually all the information in the world: the

commcomp. That was the mathematician and logician Kurt Gödel.

I reviewed the implication of P equals NP for the fortieth time, trying to determine

whether Gödel’s incompleteness theorem was an example of something that either can’t be

true or might be true. I ended up deciding that not only could this not be demonstrated,

but it led down the wrong trail. I ended up back on the thread I had begun when Mel

interrupted me in Murphy’s Tap Room and worked late into the night. I was close to

discovering the answer.

To unclog my mind the next afternoon, I went on a run down the hiking-biking trail by

the river. It was a pleasant day for it. Summer’s heat had gone, but autumn’s chill wouldn’t

come for another month. As I took Bullhook Bend, I approached a lithe figure from the

back. Her ginger curls, though not long, were bound behind with an orange ribbon, which

looked like it was about to fly loose.

It did as I neared her. I sped up and got close enough to catch the fluttering band as it

fell.

She reached behind her head when she felt it parting, slowed to a stop, turned and

gasped when she saw me. I also halted, grinned and held out her ribbon.

“Art! Where did you come from?” Her huge, luminous blue eyes held mine.

I grinned at her surprise. “I sensed a maiden in distress.”

She said, “My hair isn’t quite long enough for a ribbon to hold it, but running with it

down makes my neck sweat.”

“Turn around. Let me fix it.” When she did, I raised her curls and bound them with the

ribbon, then took out my handkerchief and wiped the sweat off her neck.

She turned to face me. “Oo, the breeze feels wonderful on my neck. Are you in the habit

of saving damsels?”

I wanted to say, none as lovely as you, but settled on, “My best talent. Shall we race on?”

“Only as far as Clement’s, where we can have a cold drink. I'm beat.”

We proceeded at an easy lope for a few more minutes until a concession stand appeared

ahead. It had service windows facing the street as well as the trail. Soon, we sat at a picnic

table sipping lemonade from clear plastic glasses.

She said, “This is the first time I’ve seen you without your tablet in your hand.”

“It’s my companion all too often. I was glad to leave it home today.”

We got to know each other. I gave her the same background information I had given

Rollie. The part about the PhD was correct. After working with computers for a couple of

years, I returned to MIT to pursue my PhD. I chose the P versus NP problem for my

research project. When my dissertation advisor, Francis Delacroix, told his friend Ben

Delgado of Szilard Enterprises about me and said he thought I had a good chance of

solving the problem, Delgado hired me. If successful, I stood to make a bundle of money

and a PhD at the same time. If I failed, at least I would have earnings from Szilard for my

current work.

Mel told me she hadn’t been in town any longer than I had. She was from Chicago and

had gotten tired of the city. Surprisingly, she didn’t speak like my cousin Rudy, who lived in

Skokie. Her accent sounded general-American with a hint of the East Coast, perhaps New

York. As a Californian, I wasn’t used to the nuances of speech in that area.

She asked, “How is your dissertation going?”

“I think I'm on the last lap.”

“When we first met and I asked if you were a scientist, you said you were a

mathematician working on a computer problem. It sounds like you cover a lot of fields.”

“I suppose I do.”

“I don’t know much about math, but I know enough about computers to manage my

commcomp. Can you tell me what your project is about?”

“It’s bad luck to talk about a dissertation until it's complete. After I submit it and it’s

approved, I'll give you a copy of it.”

She looked down, embarrassed. “Sorry, I was so presumptuous. I didn’t know –”

Impulsively, I put my hand over hers. “You didn’t do anything wrong. I'm just

superstitious.” I quickly withdrew my hand, though she hadn’t moved hers.

“Hey,” she said, “I'm thinking of fixing fettucini tonight. Why don’t you join me?”

“I'd love to. What time?”

“Around seven.”

When I returned to the apartment, I was too excited to work or even read. You can’t get so

worked up about a woman’s invitation to dinner. It means nothing romantic to her. Women find you dull.

Remember Carol. Carol moved in with me after three months of dating, the only woman who

ever had. It didn’t last long. We had too little in common; she was a chatterbox and mistook

my quiet for gloom. We didn’t argue about it, but I wasn’t surprised to return home one day

to find Carol and her belongings gone.

But I had no trouble talking to Mel. Unlike Carol, her words were substantive and

humorous, and time passed quickly. But I reminded myself that I would return to

Cambridge in a few weeks, maybe less.

On the way to Mel’s, I bought a bottle of wine. The fettucini and the cannolis that

followed for dessert were excellent. Our conversation was pleasant, as always. I found out

she was much better read in literature than me. I told myself that her choice of dinner by

candlelight wasn’t meant to be romantic.

After dinner, she showed me the paintings she had made in her studio, mostly

landscapes, with a few country scenes, but mostly of cityscapes, painted in shapes and

variegated colors of an impressionistic style, many with swirling, organic skies. A few were

of less expansive subjects: children playing in a park; stark, gritty scenes of alleyways with

fire escapes in dark, dramatic colors; and homeless people huddling in doorways. Though

the skyscrapers were too stylized to recognize, the scenes felt more like New York than

Chicago.

We had coffee in the living room, and finally, I figured I'd better leave. We both had to

go to work the next morning. When I took her hand to say goodbye, I held it a little too

long, but she didn’t withdraw hers.

We saw each other several times the next week, a few evenings for beers when I took my

work break at Murphy’s, after which I talked with Mel instead of working. Then, an

occasional lunch. I saw Rollie a few times from a distance, frowning when he saw Mel and

me together. Could he be interested in her, I wondered, or gay and jealous of her, though

he had never made a pass at me that I noticed.

On Friday evening, after our two beers, despite a sky that threatened rain, the appeal of

being outdoors, free of the summer’s oppressive heat that had reemerged that day, drove us

to walk along the hiking-biking trail by the river. The clouds increasingly glowered down on

us. The sky dribbled a few drops of rain in warning and then cut loose with the full fury of

a thunderstorm. I took Mel’s hand and pulled her toward a densely crowned pine tree.

“No, no!” she protested. “You never stand under a tree during a thunderstorm.” And

guided me toward a dilapidated boathouse.

Soon, we stood under its portico roof, drenched. Seeing her shivering in a short-sleeved

blouse, I took my windbreaker off and draped it around her shoulders. It was light but

waterproof.

“What about you?” she said. “You’re wet, too.”

“I'm fine.” In fact, standing so close to her to avoid the rain made me quite warm. “Why

not stand under a tree to stay dry?”

“If lightning strikes a tree, it electrifies the ground for a broad area around it. Anybody

standing under it is toast. Literally.”

She looked up at me, her enchanting large, blue eyes mesmerizing me, and her broad,

full-lipped mouth parted slightly. I brushed soggy red curls away from her face, bent down,

and impulsively kissed her.

I grabbed the doorknob as the kiss became fervid and intense. Miraculously, the door

wasn’t locked. I didn’t think to be surprised at finding a motorboat docked inside the

decrepit building. We descended into its cabin, rapidly pulling each other’s soaked clothes

off.

Much later, as we lay on its cushioned seat, she said, “We should go before the owner

shows up.” and snuggled up to me.

“Yeah,” I said. The rain continued to beat on the boathouse roof.

On Saturday, two opposing imperatives pulled at me: finding the answer to the P versus

NP problem and seeing Mel that evening. I knew how to solve P vee NP now. It was only a

matter of completing the unassailable proof. I could have done that by indulging in an

extremely long day’s work until two or three a.m. the next morning, as I had done until last

week. The second, far more important imperative, demanded that I see Mel that evening.

Delgado called me about mid-afternoon.

After I answered, he said, “Greetings, Art. Where’s the latest progress update? Last

week, you said you practically had a solution, so I assume you’ve either got it by now or will

in a day or two.”

“That’s not what I told you. I said I had a new approach to try. That hasn’t succeeded

yet, so I'm still working on it. I get closer all the time, though.”

“The Board’s getting antsy. Other firms are working on this. It’s even bigger than you

probably realize. Solving this will give the answer to a lot of other mysteries that not only

plague the computer industry but other technologies.”

“I'm sure I know as much about that as you do, Ben.”

“And more. But you need to give me some kind of progress report to get the Board off

my ass. Give me a completion date.”

“I can’t tell you an exact one, but I'm getting close. That’ll have to placate them.”

Delgado sighed. “Do the best you can. My ass is on the line. The president hired you

and the Board recommended you based on my guarantee of Delacroix’s endorsement.”

The call didn’t last much longer.

I had lied to him, of course. I could have had an answer to him and to MIT tomorrow. I

could still delay returning to the Szilard offices in New York for close to a week, claiming

that writing the paper containing my proofs and then submitting it to all the journals would

take that long.

But the second imperative kept me here. I wanted to have Mel as long as possible. I

knew when I left, I would lose her forever.

That night, we shared a charcuterie board of cured meats, pâtés, cheeses and bread.

Much later, when we snuggled in her bed, she said, “You’re such a mysterious man,

working on a secret project you can’t relate even to me. If you weren’t so sweet, and kind of

shy, I'd say you were an evil scientist trying to take over the world.”

I laughed. “When I finish it, you’ll be the first to know, to reassure you the world will

remain free. But I'll give you a hint tonight. To some extent, it’s based on work done by one

of my favorite scientists, Kurt Gödel.”

“Girdle?”

“That’s pretty close.”

On Monday, with Mel at work, I outlined my paper but delayed finishing it to fool myself

into thinking I had a reason to be here. That evening, at her apartment, I saw a large

bouquet of red and golden chrysanthemums in a vase in the middle of her coffee table.

“What’s the occasion?” I asked.

“My Mom had them delivered for my birthday,” she said. “She knows I love mums and

these have beautiful fall colors.”

“Your birthday is today? Why didn’t you tell me? How old are you? Twenty?”

She laughed. “No, my birthday’s tomorrow, and I’ll be thirty.”

“You should’ve told me, so I could’ve gotten you something. At least, let me buy you a

birthday dinner. Your choice of restaurant.”

“Okay. The College Inn for their shrimp special.”

“No. Not a neighborhood dive, great though their shrimp special is. Do you like lobster?

We’ll go to the Seafood Platter.”

“I love lobster, but you’re a starving PhD candidate. We can aim lower for the birthday

dinner.”

Little did she know I would soon have more money than I had ever dreamed of.

“Nonsense. Paying for a fine dinner once a year won’t break me.”

So, we dined at the finest seafood restaurant in town.

The next morning, as we went on a run, I saw she hadn’t bound her hair up in the back.

Afterward, while having coffee at Clement’s, I asked her why she had left her hair down.

“I lost my ribbon and haven’t thought to buy another. I’m accustomed to leaving it

wrapped around the stem of my car’s rearview mirror but when I went to take it down

yesterday morning for my run, it wasn’t there.”

“I suppose you looked to see if it fell to the floor.”

“Of course. I looked all over the car’s interior.”

We kissed before we left the picnic table and parted to go to our homes and showers. I

went by the flower shop and bought a bouquet of roses to have delivered after Mel

returned home from work and a green ribbon to give her that night. It should go well with

her red hair.

The next morning, I organized the maze of mathematical notes in my tablet into a

systematic form that anyone could understand. Only a section giving the proofs and a

conclusion – a half-day's work – remained to finish it. I would put that off until tomorrow.

I took a walk through a park at the edge of town where Rollie collected his bugs – uh,

beetles. As a scientist, I didn’t have the right to disparage a colleague’s profession. I hadn’t

seen him for a while and missed our visits. And as I rounded a thicket festooned with

blackberry briars, there he was.

“I’ve been hoping to run into you,” he said in his high-pitched voice.

“I was about to say the same thing,” I said. I felt guilty for not returning his calls. He had

left a couple of messages wondering if I would like to meet for a game of chess, which we

had done a few times, but I had been at Mel’s both times. We walked along together.

He said, “I get the feeling that you’re about to finish your project, and you’ll leave after

that, so we won’t be able to visit anymore.”

“Yes,” I said. “I'll be finished in a few days. But I'll be sure to come back to see the new

beetles you’ve collected.” I probably wouldn’t return, but hated goodbyes.

Rollie stopped, frowned and looked at me. “There’s something I have to tell you, Artie. I

know you’ve grown fond of Meribel, but I’ve done a bit of research on her.”

I was surprised and irritated. “Why on Earth would you do that?”

“I hope this doesn’t make you mad, but I did it out of friendship. She seemed quite

interested in you and your whereabouts during your first few weeks here. She watched and

followed you, found the house with the apartment you stayed in, and finally made your

acquaintance in Murphy’s Tap Room. She told you she worked for a trucking company.”

“So?”

“An inquiry disclosed that no Meribel McGonigal worked at Algonquin Carriers.”

I was stunned. After a moment, I murmured, “There must be some mistake….”

“I'm sorry, Artie. I'm sure there is. Just be careful.”

(TO BE CONTINUED)

Tin Cup (the second half)

November, 2024

His weapon-waving guard made him realize that doing anything would be stupid.

“Sit right there,” said the man. “Just like Duce said.”

He coughed. For the first time, Con noticed his pale, drawn face and saw him try to

not shiver.

A victim of Chou’s.

Con looked around, trying to figure out how to help Chloë and shuddering. He

wasn’t a brave man. At least there were only three men and this one was sick. From

the office, came the other two’s muffled laughter and lewd comments, furniture being

knocked around. Nothing from Chloë.

His guard slid down the wall to sit on the floor. He coughed in his hand but never

took his eyes off Con. Nor did the gun waver. They sat that way for a long time,

watching each other, Con trying not to hear sounds from the office.

Then, all grew quiet in there. Duce emerged grinning, swaggering, making sure Con

saw him buckling his belt. He grabbed the pistol and everlight from Binky’s hands.

Binky tried to stand. He collapsed. “I—I don’t think I can.”

Did he mean, take his turn raping Chloë? wondered Con. He didn’t even look able

to stand.

“I don’t think you can either,” said Duce. “Fact, you’re too sick to go any fu’ther

with us.”

Binky scrabbled to his feet. “You—you ain’t gonna leave me here!?” he whined.

“They’ll—they’ll kill me.”

“You’re dyin anyhow.” Duce swung the gun to cover Con. “You set right there, boy.

Count to a hundred before you even think a movin.” Duce backed away, holding the

gun and everlight on Con until he disappeared into the office. Con heard him say to

Chloë, “We’ll see you again, mama.”

As soon as the office door to the street closed and the light in the office

disappeared, Con leaped up and ran to it, yanked the door open and went in.

“Chloë!” Still half-blind from the everlight, he could barely see in the dark office.

“Chloë, where are you?” Not seeing her made him fear the worst.

“I’m right here.”

Following the sound of her voice, he found her sitting on the couch, her knees,

with her arms clasped tightly around them, drawn up against her breasts. When he

reached out to her, she flinched away.

“Are you hurt? Did they—”

“Do you mind getting the hell out of here while I find some clothes?”

He stumbled numbly out the door. The man the others left behind, who Con had

forgotten, had somehow gotten to his feet. Leaning against the wall, he had moved

away from the office door.

“Oh no you don’t,” Con said. He reached the man in two long strides and grabbed

his collar. “You’d ’ve done just what those other assholes did to Chloë if you

could’ve.” Con held him against the wall, feeling him tremble and trying to hold back

a cough. He wondered if his toughness was compensation for being so cowardly in

facing the others.

“I see one of ’em stayed behind.”

He turned to see Chloë standing in the office doorway, having replaced her

probably shredded scrubs with a blouse and jeans.

He said, “What’ll we do with him?”

“Did I give you all that training for nothing? We put him to bed and give him some

water.” But her stern look didn’t soften as she approached them.

“But he would’ve… I mean he—”

“But he didn’t. He isn’t able. Don’t worry. We won’t do him any favors. He knows

he’s a dead man and I won’t let him forget it.” She pulled a .38mm snub nose revolver

from her pocket and pointed it at Binky’s head. His hands shot up. She said to Con,

“Had the pistol in the cabinet but couldn’t get to it. You can bet I’ll carry it from now

on.” She nodded to Binky and to a vacant cot. Binky stumbled to it and collapsed.

“What if he’s one of those who survives Chou’s?”

“Oh, one way or the other, he won’t survive.”

Suddenly the lights and music came on. And what music! Soaring sound enhanced

by layer upon layer of added heroic accompaniment. It went on and on, ever more

monumental. He couldn’t speak for a moment after it ended. Then, “What’s that

music, Chloë?”

“Flight of the Valkyries by Richard Wagner. Noble, huh?”

“Flight of the what?”

“Valkyries. The beautiful maidens who take the souls of slain warriors to Valhalla to

party with the gods.” Then she said, “Go back to bed. I’ll watch this asshole while you

sleep.”

But Con saw her split lip tremble and the bruises purpling her brown face. He

grasped her shoulder and held it when she tried to back away.

“No, Chloë. You’ve bossed me around enough. My turn now. You go hide in the

farthest, safest corner of this warehouse and get some sleep. I’ll go lock the front door

and—”

“You can’t. They wrecked the door when they broke in. I closed it as well as I could

and braced a chair against its knob. You’ve forgotten that I’m the trained soldier and

you’re—”

“And I’m the boss now. I can see the front door from here. We’ll turn the lights off.

I can hear anyone who comes in and turn the everlight on ’em. But we won’t see

anyone else tonight.” He put a hand out and looked down at her revolver.

“Do you know how to use it?”

“Of course.” Though he had never fired a firearm in his life.

She looked down and wept. When he put her arms around her, she let him hold her

for a moment, then backed away and handed him the revolver.

“Okay, Con. You’re the boss this one time. But I’m back in charge tomorrow.”

“Of course.”

She wiped tears and mucus from her cheek with the back of her hand. “I’ve got to

clean up a little first. How I wish we had a shower.” She headed for the “Hers” door

by the office.

Con had never been in charge of anything before. He felt safe from Duce and his

buddy for the night but how would he handle an emergency with the patients? He felt

totally inadequate.

Until Gloria smiled at him.

Con couldn’t have slept, sitting on a cot next to the would-be rapist all night. The

man rolled about, groaning, coughing, sometimes talking in his sleep, much as Con

must’ve done while sick. As dawn’s first glow lightened the eastern clerestory

windows, he saw Chloë checking the patients, speaking to some. They had long ago

moved them all close together for convenience. She came to his cot, sat beside him

and smiled. She smelled like soap.

“You were right to take my place as boss last night. But now…” She put her hand

out. He handed her the revolver. Watching the sick man roll around coughing, she

said, “In spite of everything, I bet I slept better than you did.”

He stifled a yawn. “I sure hope so.”

Louie and Tony appeared with breakfast and greetings.

“Morning, guys,” said Chloë. “No one for you to take away this morning.”

“Looks like you had excitement of another kind last night,” Louie said with

concern. “What the hell happened?”

Chloë said, “Let me feed the sick ones. Tell you when I get back. I know more

about it than Con does.”

When Chloë returned, she started telling what happened the night before but

interrupted herself when she bit into the burrito. “Wow! These have actual eggs in

’em.”

“Hell yes,” Tony said smugly. “They’re breakfast burritos, ain’t they?”

“But where’d you find eggs?” asked Con.

Tony said, “Folks had chickens in the ’hoods. The folks is gone but the chickens

ain’t. They’re ours now. We git the food we bring you from them folks’ houses.”

Then Chloë returned to her version of what happened. Con recognized it as

sanitized bullshit, but she interrupted him whenever he tried to interject something.

She waved toward Binky, who mumbled in his sleep. “This one was in better shape

last night. He held a gun on Con so he couldn’t do anything.”

Louie said, “I can tell these shitheads hurt you worse ’n you’re tellin us. And it’s

possible they’ll come back.”

Chloë said, “They found out we don’t have any drugs.”

“But that Duce creep,” said Con, “told you he’d see you again.”

Tony said, “Remember, they think there’s only two of you, stuck here because of

these sick folks. And good luck getting police protection.”

“But,” said Louie, “there’s an easy way out of this.”

“I’m glad you can see it,” said Con.

Louie said, “It’s something we all been missin. Just like you got empty beds here

because of the folks we carry out, the hospital must have even more. They’ll take

these few folks that are left.”

Chloë smacked her forehead. “You’re right. How dumb of me. The hospital

should’ve thought of this too.”

Louie shook his head. “They got problems of their own, prob’ly don’t think of

outlier clinics like this.”

Chloë stood up. “I’m gonna call them right now. That is if my damned phone still

works.” She stalked off toward the office.

Con asked, “What are you guys gonna do when food in the houses runs out?” He

worried about what he would do.

“The wife and me always had a garden,” Tony said. “I’m plantin a bigger one. As

soon as our work here is done, like maybe tomorrow if the hospital takes these sick

ones, we’ll scour the countryside for livestock.”

“I always been a city boy,” said Louie, “but Tony here was raised on a farm down

Escondido way.”

They, or rather Tony, talked about farming until Chloë returned, holding her phone

and looking relieved.

“They’ll send ambulances sometime this afternoon,” she said. “But I got the police

voicemail telling me to leave my number and they’d call back.”

By mid-afternoon, no ambulances had arrived, and the police department had not

answered Chloë’s call. When Chloë called the hospital, they said drivers had been busy

bringing multiple casualties from a riot at a food distribution center and an

uncontrolled fire in the south end of town. They would make two ambulances

available for them first thing in the morning.

Tony said, “Like I said earlier, good luck gettin help from the cops. Or any other

so-called public servants.”

Con shuddered. He hadn’t thought of living without police or fire protection.

Pointing to their sleeping captive, he said, “What do we do with him?”

“Well,” said Louie, “he needs to tell us where his buddies hang out so we can tell if

they’re close enough to come back tonight. Why don’t you two,” nodding to Chloë

and Con “go wait in the office. Chloë, can we get outta one of them doors?” He

pointed to the large rear truck entrances.

“No. They welded them shut when they made this a clinic but there’s an employee

entrance at the north end of the building. It’s locked, barred and chained on this side,

but you can get out.”

Con said, “But what are you going –?”

Chloë said, “C’mon, Con. This is Louie and Tony’s business.” And to Binky, “I’m

officially discharging you as my patient, you son of a bitch.”

Binky whined, “No, please….”

She took Con’s arm and led him to the office. Louie and Tony roused the weakly

protesting Binky and half led, half dragged him toward the north end of the building.

Con saw the wrecked office for the first time in daylight: overturned furniture, the

contents of shelves and filing cabinets dumped all over by Duce and his pal looking

for drugs. The chair Chloë had jammed against the door could not have stopped a

determined intruder. While he helped her straighten the mess, she packed a suitcase

and backpack. She would leave for Colorado as soon as the patients had been taken.

He would also go, so he packed his meager belongings in a knapsack that had

belonged to a patient.

He tried not to hear the muffled cries from behind the building where Louie and

Tony had taken Binky.

When Louie finally entered the office, Con said, “Binky—?”

Louie frowned and shook his head. “Another victim of Chou’s disease.”

Chloë looked at Con. “We did our part, took care of our patient. But I told you he

was a dead man.” And asked Louie, “Did you find out where the others are holed

up?”

“Down by the river. That’s so close Tony went to get stuff to fix the door in case

they come back. We’ll stay here tonight.”

After Tony returned with tools and lumber Con helped the two barricade the

broken front door and add support to the plywood-covered front windows. That

made the employee entrance the only exit, but no one could get in from outside.

They finished by evening. The electricity had been off all day. Like the other three,

Con would leave as soon as the ambulances left in the morning, but he didn't know

where he'd go. His apartment held too many memories to return there.

Louie had also brought bread, sausage and cheese. They left the dark office to eat

in the warehouse, where a little light peeked through the clerestory windows. Chloë

fed the patients first and then joined the others. They talked in a desultory fashion, a

little nervously. Con hoped last night’s mayhem would satisfy Duce and his remaining

crony for several nights. Then he and the others would be gone. But he had seen rifles

Tony had brought with the tools and lumber just in case.

At last, Louie stood and stretched. “I’m for turnin in,” he said. “I’ll stay in the

office with you, Chloë, if that’s okay.”

“Sure.”

“And I’ll stay by that locked door at the end of the building,” said Tony, “even

though I know nobody can get in.”

Con looked up at the clerestory windows. “What about them?”

Chloë said, “They can’t get in up there if that’s what you mean. That’s where I slept

last night, thanks to you for letting me get my shit together, the safest place in the

warehouse.” She pointed to the catwalk under the eastern clerestory windows across

from the office.

Con said, “That doesn’t look too safe to me….”

“That catwalk’s thirty feet high and there’s no way to climb up the outside wall.”

“But still….”

Tony said, “If you think them guys can fly through them windows why doncha take

some bedding up there and spend the night.” Just humoring the over-cautious kid,

thought Con. “Here.” He held out a sleek, futuristic-looking pistol.

“He wouldn’t know how to handle one of those new German Kromachs,” said

Chloë. “I’ll take it and give him my old Smith & Wesson.” She handed Con her

revolver and took Tony’s pistol. “Just stay away from the railing, Con. It needs fixing

in places.”

Con chose a place on the catwalk directly across from the office. Though not

especially afraid of heights, he found the thirty feet from the catwalk to the floor

intimidating. Looking down from near the top of the ladder had been a mistake. From

there, with the floor invisible in the dark, it felt like peering into a bottomless pit.

Because of that and the weak railing, he unrolled his bedding against the wall.

Tony had set up a cot by the employee entrance at the north end of the building

thirty yards or so to his right. Con opened a clerestory window—it squealed from lack

of use—and looked down. Indeed, the concrete paving lay as far below as the floor

did inside and he saw no way anyone could climb the smooth outer wall. He closed

the window—another screech. Because of his sleepless night watching Binky, followed

by work in the office that afternoon and the stress of the Duce guys’ invasion, he

soon fell asleep.

Harsh sounds coming from the office awakened him. No, from outside the office,

pounding on and rattling the boarded-up front door, beating on the plywood-covered

windows, loud voices muted by walls and distance. But more than just two voices. The

noises ceased; he lay listening, his heart pounding.

A truck pulled up to the building’s rear, larger than a pickup. He jumped when

something bashed the huge, welded truck doors below. He prayed they would hold.

Then quiet. The truck didn’t leave.

Time crept by.

Then, impossibly, thirty or forty feet down the catwalk in Tony’s direction, a

clerestory window shrieked. He grasped the revolver in one hand and withdrew the

everlight from his belt, moved silently to his knees and then to his feet. Kicked the

bedding out of his way. A figure filled the open window, dark against the moonlit

night, and dropped to the catwalk. Another followed him. And then two more. The

first one looked outside the window and down.

Con barely heard the second one whisper, “Whatcha lookin at?”

“Makin sure Dick drives round front and waits. We four can take care of that

dipshit kid and the woman. He’s toast and she goes with us.” Duce’s voice.

Con could only avoid becoming toast by striking first. He steeled himself, rubbing

the sweaty palm of his gun hand against his jeans.

Another man whispered, “Where’s the stairs down?”

“Fuck if I know. Get to lookin for ’em.”

Con switched the light on and trained it on Duce’s eyes and the revolver on his

body. He pulled the trigger. It didn’t fire.

When Duce fired, his pistol’s report sounded preternaturally loud so near the

ceiling. But he missed, probably blinded by the everlight. In panic, Con hurled the

worthless revolver at Duce, who dodged. It struck the next man who stumbled back

into the third. Con kept his everlight trained on Duce’s face and desperately charged,

sidestepping another shot on the way.

Though a poor high school football player, when Con’s outstretched fist hit Duce

in his solar plexus, he went down. But so did Con’s everlight, right over the edge of

the catwalk, making him as blind as the others in the dark. And they had all the guns.

Con stumbled and fell on Duce.

No, not quite as blind. He had stood behind the source of light directed at their

faces. With Duce and Con down together in the dark, the other three dared not fire.

Con disentangled himself from Duce and scooted back to sit against the wall.

Stunned, Duce struggled to stand. Bending his knees and drawing his feet back, Con

straightened his legs and struck Duce as hard as he could with both feet. Half

standing, Duce stumbled into one of the other men, who lurched back against the

railing, crashed through it and fell screaming to the floor below.

Con stood and turned toward the ladder, knowing he had little chance of making it.

He heard footsteps. A hand grasped his shirt collar and slammed him against the wall;

Con recognized Duce’s short blondish companion from the previous visit.

“Lemme have him,” Duce snarled. He grabbed Con’s shirt front, elbowed the little

guy away and said, “Okay, dipshit. You’ve caused us enough trouble. I’m not gonna

waste a bullet on you, though. You’re gonna go right over the edge—”

A shot came from below. The little guy crashed against the wall and slumped to the

catwalk floor. Duce whipped Con around to stand between him and whoever fired,

his forearm tight across Con’s throat. Con looked down. Tony pointed his rifle and an

everlight up at them.

“Let the boy go,” Tony said calmly, “and we’ll let you leave however you got in

here.”

Duce said, “Sure you will, Pancho. I got a better deal for you. You put your rifle

down on the floor and walk away. Then I’ll let the boy go.”

Tony lowered the rifle but kept his light trained on the two. What!? thought Con

frantically. Is Tony believing this asshole!?

Another shot, this time from the direction of the office. Duce lurched, clamped a

hand over blood spurting from his neck and struggled to keep standing. Pulling

frantically out of his grasp, Con pushed him against the railing and watched him fall

through it. Con was vaguely aware of the fourth man escaping out the open clerestory

window.

He looked down. Chloë stood in the office doorway, lowering a rifle to her side.

Of course! With him and Duce facing Tony at the building’s north end, a good

marksman in the office doorway would have a clear shot at Duce’s left side. That’s

why Tony held the light on them even as he lowered his rifle.

They heard nothing from the thug Duce had ordered to go to the front or the one

who escaped out the window. The sound of gunfire, Chloë said, must have made him

decide discretion was the better part of valor and he fled into the night. They sat in

the dark office, weapons ready, though they didn’t expect any more violence.

After Chloë returned from explaining to her patients what had transpired and

reassuring them, they discussed the raid. Duce and his remaining partner had brought

buddies along. Chloë shuddered when she mentioned their intent to abduct her.

Louie had retrieved Chloë’s 38mm snub nose. He laughed. “It’s no secret why the

gun didn’t go off. The safety was still on.”

“I'm wondering how they got up to them windows,” said Tony, “but I got no

interest in goin out for a look-see in the dark.”

Con knew the other three could easily have defeated the thugs without him. Duce’s

guys didn’t know about Chloë’s revolver or Tony and Louie’s presence. They

nevertheless treated Con with more than warranted esteem. In case they thought he

threw the first thug off the catwalk, he didn’t tell them otherwise.

As weariness replaced their adrenaline high, they began to realize how tired they

were. Hours had passed. Dawn would soon spread her rosy fingers across the high

windows.

Tony said, “Okay, it’s time the rest of you hunkered down for some sleep. I’ll keep

watch.”

Just as Con started to doze off, the lights blossomed and the music came on, a rip-

roaring thundering that sounded like celestial beings galloping overhead.

“There it is again!” said Con. “The Lone Ranger theme!”

“I never heard of no ‘Lone Ranger’,” said Louie.

Chloë chuckled. “He was an old-time cowboy character in the days of Western

videos. This is his theme song. It’s a movement from an overture written long before

the Lone Ranger came along by an Italian composer named Gioachino Rossini, the

William Tell Overture.”

“See,” Louie said to Con. “I told you she knew all about this classical shit.”

Chloë said, “My grandma told me it was so famous as the cowboy’s theme song

that the word ‘intellectual’ came to be defined as someone who could listen to the

William Tell Overture without thinking of the Lone Ranger.”

Gloria holds out her arms to him. Her look of longing breaks his heart. He asks,

Why did you leave me? Will you stay with me now? She smiles sadly. She seems to say, I’ll

always be with you. He reaches for her but can’t touch her for some reason. She grows

pale, no, fades to translucence. But you can go to Chloë, Con. She continues to fade.

Gloria, come back. He can scarcely see her. She smiles wanly and disappears.

He sat up abruptly, shaken by the dream. Only Tony sat there to wish him good

morning.

“Louie went to our place to get us something to eat,” Tony explained. “I told Chloë

we’d wait for the ambulances, so she got her bags and took off.”

“I wanted to say goodbye to her,” said Con.

Tony shrugged. “Said she couldn’t stand goodbyes.”

When Con went to care for the patients, he was delighted to see Ms. Taylor sitting

up. She looked weak but smiled up at him. “I’ve quit coughing, Con,” she said. “And

the fever’s down.”

Con grinned. “Chloë told you that you’d walk out of here. Chloë never lies.”

He found Mr. Mercer also feeling much better and the young woman Lucy sitting

up.

Tony turned on the music and when Louie returned, they ate with Flight of the

Valkyries playing in the background.

He said, mostly to himself, “I wonder if there’s any Black Valkyries.”

Louie said, “I don’t know much bout stuff like that but I spose so.”

After they finished eating Louie said, “I found out how those assholes got in the

window last night. There’s a flatbed truck under it with a long extension ladder on the

bed. They wrapped gunny sacks around the upper ends they laid agin the building to

muffle the noise.”

“Wonder why the truck’s still here,” said Con.

“I’ll bet the keys are in Duce’s pocket.” Louie nodded toward the employee

entrance. They had piled Duce’s and the other corpses outside it.

“I see you’re ready to leave, too.” Louie nodded at Con’s knapsack.

“Yeah, as soon as the ambulances get here.”

“You don’t need to wait for them,” said Tony. “We’ll be here. But you’re welcome

to come home with us.”

He shook his head. “Thanks, guys, but I have too many memories here.” He

hoisted his knapsack onto one shoulder and stood up.

“Then where will you go?” asked Louie.

Gloria’s sad smile from the dream lingered with him. In it, she had given him

permission to seek out Chloë. But how did he feel about Chloë?

He only knew one way to find out.

“I think I’ll head for Tin Cup.”

AMR Denial

November, 2024

In the last post, I described the rise of antimicrobial

resistance (AMR) and how quickly it has expanded since

antibiotics came into broad use at the end of WWII.

(The first antibiotic, penicillin, was discovered by the

doctor and researcher Sir Alexander Fleming in 1928,

but it wasn’t widely used until the end of WWII in the

1940s.)

Humanity has long been in denial of the danger or even the existence of deadly diseases.

Coverup and disbelief helped spread the so-called Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918-1919.

The nations locked in World War I hid the number of cases from their enemies. It became

known as the Spanish Flu because Spain, which remained neutral, factually reported the

spread of the disease. No one knows where the flu strain began, but the first recorded cases

were in a US Army camp in Kansas.

By the end of 1919, it had infected a third of the world’s population and killed around 50

million people, including some of my ancestors. And probably some of yours. By the latter

part of 1920, almost no one spoke of it, as though refusing to mention it meant it never

happened.

The most recent major disease that faced denial is the COVID-19 virus, which caused at

least three million deaths worldwide and a million deaths in the US in 2020 and 2021.

Without the advances in medical science over the last century, the number of deaths would

have exceeded those of the 1918 – 1919 pandemic.

Of the half-dozen people I personally knew slain by COVID-19, the first was my

accountant and friend while he prepared my income tax return. I canceled my appointment

with him to discuss it as COVID-19 became a pandemic and handled it by email and

phone. He scoffed, saying he didn’t worry about catching it because he never got sick.

He contracted the disease and died in the hospital in March 2020.

Most of the victims I knew either echoed my accountant’s reason or argued the danger

was exaggerated. The last of the six I knew claimed both: that he never got sick and the

disease was only a slightly worse strain of the flu. That he stayed free of infection while

working in a store, maskless, throughout 2020 and early 2021 “proved” he was right. Until

he died of the virus in February 2021.

Some acquaintances exposed themselves to COVID-19 without getting infected.

Entertainers I knew performed more or less regularly (until their venues wisely shut down).

Others attended live shows without harm. That they escaped the disease gave them

“evidence” of how overblown the fears of people like me were.

Antimicrobial resistance is spreading at an alarming rate and people either don’t know

about it or discount its seriousness. This is due to the reticence of scientists, the dearth of

warnings by the media and a general lack of knowledge, though a few articles about the

dangers of AMR have finally begun to appear in some major news providers.

Tin Cup (the first half)

October, 2024

Con awakened, unable to breathe. He sat upright in panic and coughed his air passage

clear, shooting sputum to the foot of the bed. He fell back, exhausted, still fighting for

every breath. His chest ached.

He half remembered rolling around feverishly in his sleep. Feeling cold, he wrapped the

blankets tightly around him and slept again, more or less. Ragged coughing and weird

nightmares he half-remembered shattered his sleep. Feeling the urge to go to the bathroom,

he writhed to a sitting position, scooted his feet off the bed and stood on shaking legs. The

fever had returned. With his first steps, he broke out in a cold sweat, felt lightheaded and…

… woke up face down on the floor lying in his own piss.

The Disease had stricken him again. This time, he would die. At less than twenty-five

years old.

Suddenly he didn’t want to die at home alone as his mother had chosen to do.

Somehow, he got cleaned up and dressed. Unsure of the time, it felt like mid-morning

when he got down to the street. With a sky appropriately overcast for the day of his death.

A chilly wind blew trash and leaves down the deserted street. He inched along by hugging

the buildings. He couldn’t make it all the way to Metro Hospital but might to the nearby

clinic, an abandoned warehouse adapted to care for overflow victims of the pandemic. He

had taken Gloria there. They had few medical supplies. No drugs existed to fight Chou’s

Disease, a bacterial infection resistant to all antibiotics. They just made you as comfortable

as possible and kept you hydrated. Then you either came out feet first or, less often, on

them.

Traffic would have made crossing the intersection at the end of the block harrowing. He

had heard no cars pass his apartment for weeks, though modern electric and fuel cell cars

made virtually no sound. And, unheard of on busy San Juan Obispo Boulevard, none

appeared on it. Feeling faint after he crossed, he slumped against the first building,

coughing. After a brief rest, he pulled himself along by clinging to the buildings. His chest

still hurt, and he felt the fever increase. He had heard that, at some level, fever caused brain

damage, though he didn’t know what it was. But, he thought ruefully, what difference did

that make to a dying man?

Only one business remained open, Lam’s Quik Stop, in mid-block. The old Asian guy

who managed it stood alone behind the counter, looking small among the mostly empty

shelves. Customers had bought almost everything after the news identified Chou’s Disease

as a pandemic. Wholesalers no longer resupplied the stores. Lam stared impassively straight

ahead.

Con made it another block. And another. Then, turned left onto Oak Street and went a

little farther. And there it was. You had to know it served as a medical facility. It bore no

identifying sign, not even that stick with the wings at the top and the snake wrapped around

it. Or maybe two snakes. He couldn’t remember which.

He opened the door to what had once been the warehouse’s front office. This time,

dizziness and nausea warned him he was about to faint. He made it to a chair facing a

desk…

… and woke to someone mildly shaking him. He looked up into a middle-aged Latino-

looking man’s concerned face.

“Are—are you a doctor?” Con rasped.

“’Fraid not, man. I just help carry out the ones who don’t make it. Chloë figured you was

sick and sent me in here to see how bad.”

The ones who don’t make it. He shuddered.

“Here,” said the man. “Let me get you to a cot. Chloë’ll see you soon as she can.”

Even weaker now, Con couldn’t have stood without the man’s help. He led him through

a door into a vast, dark area filled with rows of cots, most empty but a few with figures

huddled on them. The man helped him to a cot near the office door and covered him with

a blanket. He didn’t know anything else for a long time.

He awakened muzzily, confused. Above, girders holding up a high ceiling reminded him

that he had come to the warehouse. Just under the ceiling, filthy clerestory windows stared

from all four sides of the warehouse. A little light peered timidly through the eastern ones.

He had slept the previous day and night away. He had never been so thirsty. And weak.

Sitting up would prove challenging, but his bladder insisted on it. Fortunately, his and hers

bathrooms lay near the office’s back door, only a few steps from his cot.

When he returned to plop down on the cot, his head swam for a few moments. He

remembered how Gloria had looked on one of those cots, shriveled and wan. He would

never hear her earthy, vivacious laugh again.

He coughed, but only a few little hacks. Surprisingly, he felt marginally better. His fever

had gone down and his chest no longer hurt. Music came from somewhere above, not the

mindless tinkly crap you heard in public places but classier stuff.

Looking around for a source of water, he wondered at the small number of patients.

When he had brought Gloria here, they had occupied nearly every cot. The latest news he

heard, maybe a week ago, had said a cure was imminent. But the vacant streets—the only

cars on them had been parked—seemed an ominous sign to the contrary.

Someone in blue scrubs several aisles over rose from crouching over a patient and

looked his way. She stood and strode purposefully toward him, a tall Black woman. He

vaguely remembered her rousing him in the night to give him water. Despite her large,

muscular frame, she moved with sinuous grace. As she drew nearer, he saw the stern, tired

look on her face. She was all business, this woman. When she stood over him, he realized

she would have been pretty without that severe expression. She wore her hair in dreadlocks

wound about her head in a complex coiffure, revealing a long, elegant neck. He

remembered that some African queen had had a famously beautiful neck. He couldn’t

remember her name.

“Don’t spill any of this,” she said, thrusting a beaker of water toward him. “We don’t

know how much longer we’ll have any.”

He took the beaker and drank thirstily, and then said, “What do you mean? Why won’t

we have water?”

“Haven’t you noticed the lights flickering on and off? It’s only a matter of time before

Pacific Gas and Electric shuts down altogether. A utility provides the water too, albeit a

City one, the Tres Robles Water Department. They’ll run out of potable water sooner or

later.”

“But I’ve got Chou’s again,” he said glumly. “I won’t need water for long.”

“Your second time huh? People seldom get it again, but if they do, it’s a lot milder. You’ll

live. Quit feeling sorry for yourself.” She produced a tablet from her scrubs. “What’s your

name?”

“Huh?” He had hardly heard anything she said after she told him he’d live.

“I need your name, social, next of kin, stuff like that for the record.”

“Oh, sure. Conrad Quinn Colby.” He choked up to think he no longer had a family but

gave her the other information.

“I’m Chloë.” He had sat up a bit to drink. She took the beaker and pushed him down

more gently than he would have believed from her brusque voice. “Now rest. You’ll be

weak for a few days, but when you get up, I need some help around here. You probably

don’t have a job to go back to.”

Con’s job had indeed disappeared along with most others. The pandemic had either

killed off employees or made them fear infection too much to go to work

She wrapped a blood pressure cuff around his upper arm, watched the readout and

listened to his heart through a stethoscope.

Con said, “That sure is some old-fashioned medical gadgets.”

“Blood pressure cuffs have been around since the 1850s, so I trust ’em. These ‘medical

gadgets’ work even during power failures.” Then, “I’m sure you’re hungry. When our Good

Samaritan gets here, he’ll give you something to eat.”

Again, it struck him: he would live! He had grown used to the idea of dying and almost

welcomed it after the death of his mother, his girlfriend Gloria and his friends. Survival

brought up other problems. He would have to find food and—a problem he hadn’t known

about before—water.

Surprisingly, since he hadn’t eaten for a couple of days, he didn’t feel hungry, just

extremely tired. He slept again.

He awoke in the night in complete darkness, thinking of Gloria, then of the ones he

would never see again—his mother, drinking pal Henry and others. Similar demons must

have haunted the old Asian convenience store guy. He thought he had finished crying, but

he wept again.

When he dried his eyes, he realized he had to leave as soon as he felt up to it. He didn’t

know where to go, but the neighborhood held too many memories to stay.

The darkness wasn’t quite complete. A sliver of moon shone through a clerestory

window, fuzzily through the filth. And stars! Bright artificial light so close to downtown had

always blotted out the starlight. The street and building lights must have gone out, as if

presaging the death of all the world.

The next morning, Con realized he felt much better and his appetite had returned. The

electricity had come on. The galloping theme from the ancient Lone Ranger television

show played. The Latino guy who had greeted him approached bearing a wire basket full of

little cloth-wrapped packets. When he reached Con, he handed him one. It felt warm and

smelled heavenly.

The guy said, “You look a lot better than when I first saw you, kid.”

“Yeah, Chloë said I was gonna live.” He extracted a tortilla wrapped around something

and bit into it. Fried potatoes. After a couple of bites, embarrassed for not thanking the

man, he said, “S-sorry. I was really starved. I sure appreciate—”

The man waved his apology away. “Not to worry. Sorry it’s so little. I haven’t been able

to bring much food in lately.”

“You must be the Good Samaritan Chloë told me about.”

He nodded. “Otherwise known as Louie though sometimes Chloë calls me Charon.”

“Kare-on?”

“Yeah. Some kinda god that took dead people away, like Tony and me do from here. We

didn’t know who he was neither till she told us. She’s into that mythology shit. And classical

music. She programmed the music you hear.” He pointed at speakers positioned high above

the room.

“Well, I’m Con,” Con said around a mouthful of breakfast. “You guys wear a lot of

hats.”

“Yeah, we took a couple more out this morning. Ain’t many left.” Louie looked away

grimly. “Glad to see you’re doin okay, kid.” And he turned away.

Con finished eating and sat up. He wished the burrito had been bigger. He felt weak but

Chloë had said she needed help, and he had nothing else to do. He got up and looked

around for her. Hearing a voice in the office, he opened its door. Chloë sat behind a desk

talking on a cell phone. He hadn’t noticed much about the office when he first stumbled in.

In addition to the desk, its chair and two chairs in front of it, there were filing cabinets, a

conference table surrounded by chairs and a sofa with rumpled bedding, apparently her

bed. The front windows had been boarded over with plywood. She motioned him in while

she talked. He sat in one of the chairs before the desk. She looked tired.

After she finished the call, she said, “You look like you feel better today.”

“Yeah. I’m ready to help you out.”

“Okay, good. There’s less to do now but I’ve been doing it all for almost a month, day

and night. I need some sleep bad. Let me show you what to do.” She stood and led him out

into the warehouse. “Not many new cases come in now. Most don’t make it past a week.

The ones still here have suffered longer. Some may survive but not many. I feel so sorry for

them.”

He followed her down an aisle between cots. “Are you a doctor?”

“No. I was a medic in the Army, a lab tech in a CSH unit. That stands for Combat

Support Hospital.”

“Wow. So, you saw combat. In some pretty grim places, I bet.”

She scoffed. “Yeah. Youngstown, Ohio. Huntsville, Alabama. Down in LA. I’ve been out

of the Army for a while but when I ended up in the hospital for something other than

Chou’s—I'm one of the few it didn’t infect—they checked my record and shamed me into

working here. My replacement’s coming next week, though, a Dr. Worth, and I’m out of

here.”

“Where will you go?”

“I was on my way to join my boyfriend in Colorado when I ended up in the hospital.”

She looked away, trying to keep him from seeing her tearing up. They both knew Chou’s

Disease had probably taken him. “Tin Cup, Colorado.”

“That’s a weird name.”

“Yeah. It’s on a mountain ridge. Remote. Isolated. The world has gotten so fucked up,

with oceans rising and dying, people fighting for food and living space, we wanted to get

away from it. He bought a restaurant up there.” Her voice cracked and suddenly turned

brusque. “Here’s what you’ll do. Give them plenty to drink and food when Louie comes

around, talk to them a little, even if they don’t respond. When they foul their bedding, you

change it and clean them up. I’m way behind in the laundry room. We can catch it up now

that there’s two of us….” She followed with more instructions. Then paused beside a

middle-aged woman’s cot, one who had, Con could tell from the smell, “fouled” her

bedding.

Chloë smiled. “How’s it going Ms. Taylor?”

Ms. Taylor, her face drawn and pale, looked up at her sheepishly. “I messed up the bed

again, Dearie.” Her voice broke up in a coughing fit. Her eyes filled with tears. “You’ll have

it easier when I’m gone.”

“I sure will, Ms. Taylor, and so will you when you walk out of here on your own two

feet.” She put her hand on Con’s shoulder. “See this scrawny brat here. He made it. So will

you.”

Gently, treating Ms. Taylor like her only patient, she demonstrated how to change the

bedding with her on the cot, rolling her gently at the appropriate times. Con wondered

where she found that reservoir of strength and patience.

As they walked on, Chloë paused to pull the blanket up over an unconscious man. She

said, “Mustn’t keep kicking that blanket off, Mr. Mercer. It gets chilly in here.”

An emaciated young woman on the next cot made motions indicating her thirst. Chloë

poured water into her cup from the bottle she carried. She had to hold the woman up far

enough to drink. “That’s it, Lucy. Drink the whole glass.” And to Con, “Lucy is badly

dehydrated. Make sure she has plenty to drink.”

Con thought Louie and Tony would be carrying Lucy out soon. He wondered how

Chloë could stand living among all this tragedy.

Chloë said to him, “Think you got it?”

“Yeah. Looks pretty straightforward.” In truth, it looked daunting. But he was glad to see

no children. He knew they and the elderly had gone first.

“I’m going to take a nap in the office. You’re still weak, so when you start to flag, come

wake me up.”

“Sure, Chloë.”

So, he got with it. He gave patients water and spoke to them. When Louie brought food,

he helped pass it out. He found the rest of the work the most repugnant he had ever done.

He emptied bedpans, wiped asses and changed bedding. Gloria had often chided him for

being self-absorbed. Unsure what that meant, he nevertheless recognized it as

uncomplimentary. He smiled sadly. See how unself-absorbed I am now, Babe?

Only thirty-three patients remained. He wondered how Chloë had managed when she

had had fifty or a hundred. His admiration for her grew. Though still weak, he worked until

she returned five hours later.

“You should’ve called me a couple hours ago,” she scolded. “You look beat.”

“No, it was a piece of cake.”

Though Chloë tended to boss him, Con couldn’t feel irked by someone with never-

flagging patience for her charges. But to spare him, she often called him too clumsy and

shooed him away from the messier clean-up jobs. He loved watching her move with quiet

grace among the cots. Though never seeming to hurry, she always accomplished more than

he did. When they worked at the same time, he spent the shift in the laundry room. In a

few days, he had caught it up.

He finally remembered the name of the African queen known for her beauty and her

graceful, elegant neck: Nefertiti.

On many days, Louie and Tony took the dead away. For Con, they changed from bodies

on cots to people under his care, friends. After a week twenty-six remained.

One evening in the office they finished a meal of steamed vegetables and some gamy

roasted meat—Con didn’t want to know its origin—that Louie had brought. The doctor

replacing Chloë would arrive any day. Con would miss her.

He asked, “Are you still planning to go to that Colorado town?”

“Tin Cup. Yes.”

Looking down, he said, “I was just wondering, uh….”

“Yes, we know Carl may not still be alive. But I promised him I’d come.” She said

nothing else, but Con could feel her looking at him. “Con.”

He looked up at her intense gaze.

“How old are you? Twenty-five?”

“Y—yes.” He was twenty-four.

“Well, I’m thirty-two. I’ve grown to like you, and I really appreciate your help, but I feel

more like your big sister.”

“Well, shit, Chloë….” He got up and stalked out of the room. She had mistaken his

concern for her safety while traveling so far for a more intimate feeling. He loved only

Gloria, now lost to him forever.

By the tenth day after Chloë talked to the doctor, he still hadn’t arrived. Louie and Tony

left with two more bodies. Only nineteen patients remained. Con figured the doctor hadn’t

come for fear of infection. The electricity, and thus the lights and music, stayed off for

longer periods. It had been off all that day. Little light came from outside on that moonless

night but Con and Chloë had everlights that the sunlight charged by day.

Because of the increasing violence outside that Tony and Louie told them about, Chloë

and he took turns keeping watch at night. It was her turn. Con lay on his cot, the same one

he had first occupied, reading a paperback book a patient had left behind. After a time, he

drifted off….

A sudden crash, then blinding light and loud voices, awakened him. He sprang to his

feet. A hand against his chest roughly shoved him back to a sitting position on the cot.

“Stay right there, pal, and you won’t git hurt. We’re just lookin for drugs.”

Con said, “We don’t have any—”

A hard blow to the side of his head made it spin.

“Shut the fuck up. This is a hospital ain’t it?” The blinding light from the man’s huge

everlight didn’t keep Con from seeing the 9mm he held in front of his nose.

“Yes, but…”

“Then tell us where the drugs is at or you’ll git another dose of this.” He shook the pistol

in Con’s face.

“Hey, Duce,” came a voice from the rear of the warehouse. “If they ain’t got no drugs I

found a toy for us to play with.”

Duce turned his everlight on a small blondish man forcing Chloë toward them with a

hand grasping her upper arm and a pistol held to her temple.

He chortled. “This big mama’s got enough love for all of us.”

Stunned, Con jumped up.

“Sit down, Con.” Chloë demanded in her bossiest voice. “This doesn’t concern you.”

Grasping Con’s shirt front, Duce pushed him down to the cot. He had discolored teeth

and liquor-stinking breath. “Better listen to big mama,” he hissed.

Duce turned to a third guy leaning against the wall, handed him the pistol and everlight